Sergio Diaz enthusiastic security engineer

Am I Designing A Safe Password Storage

Photo by Matthew Brodeur on Unsplash

This blog post exemplifies and covers how a password storage should (or shouldn’t) be designed.

Data Breaches are Everywhere

Nowadays is not uncommon to read about a data breach. These incidents happen everyday and there is no sign that they will stop any time soon. Personal Identifiable Information (PII) such as emails, passwords, and addresses are out there in the wild and unfortunately it is too late to fix the roof when it is already raining.

A breach can occur due to several reasons such as insider threats, bugs, or misconfigurations. Sometimes these factors might be out of the engineers’ hands, but something that definitely is in their power is designing by assuming that data will be compromised.

Plaintext Passwords

Let’s start with the most straightforward way on how not to do it: storing passwords in plaintext.

If a breach happens, an attacker wouldn’t need to even move a finger in order to see any user’s password. Furthermore, this might have more impact than it seems. For example, following this bad practice could mean that there is no data sanitization which might lead to other security concerns such as Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) or SQL injection (SQLi). Also, according to a study made by pandas security, 52% of users have the same passwords (or very similar and easily hackable ones) for different services.

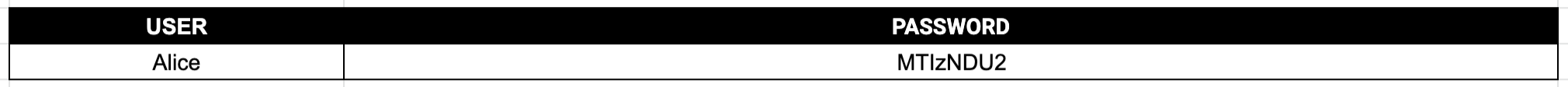

Let’s say Alice uses the same password for site X and site Y. Even if site X is super secure, all it takes is a breach from site Y in order to get the password for site X. After all, a chain is as strong as its weakest link.

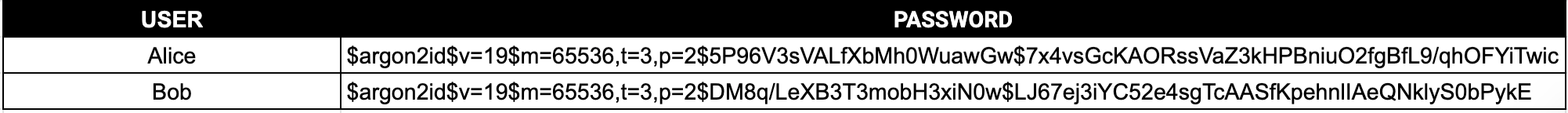

Site Y’s plain-text database

Encoded Passwords

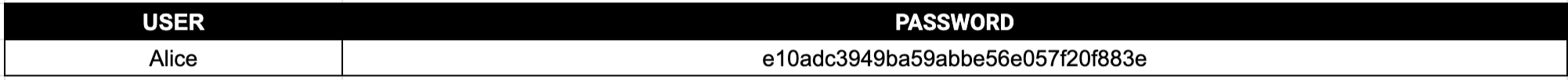

Take a look to this string: dGhpcyBpcyBlbmNvZGVk

This looks like random one right? Not so fast. If we take a closer look we can see it is encoded. This means that the data has been transformed so it can be properly and safely consumed by a different type of system. The goal of encoding is not to keep information secret, but rather to ensure it is able to be utilized properly by another system (binary data, emojis 🤙, etc). If engineers store passwords by encoding them, is practically the same as storing them in plaintext. Why? Because everything that is encoded can easily be decoded by using any programming language or sites such as https://www.base64decode.org/.

Site Y’s encoded database

So even if Alice’s password looks that it has been obfuscated it is not. Now that you know how to decode a string can you decipher Alice’s password?

Hashed Passwords 1.0

Previously, it was mentioned that everything that can be encoded can easily be decoded. What if there was a way to “encode” something without the possibility of being “decoded”? Well, that’s exactly one of the main properties of a good hash function. If you have the output of a hash, you cannot reverse it in order to determine the original input. In other words, hashing is a one-way function (irreversible).

Another property of a good hash function is determinism. This means that every single time 123456 is hashed with a specific hash function, the result will always be the same. This is great, because instead of storing a password you store the hash value of it.

Using a hash function to store passwords is quite clever, because here is where engineers can take advantage of the the two properties that were just discussed:

- Irreversibility

- Determinism

On the one hand, if someone sees the hash value of the password she will not be able to reverse the it in order to obtain the original password. On the other hand, each time a user logs in, she will type her password and the application will hash the value of it. If the stored hash is the same as the recently computed one, access should be granted, otherwise it should be denied.

Site Y’s MD5-hashed database

So this is it? As long as engineers apply a cryptographic function to a password storage it should be secure, right? Not so fast. There are many hash functions out there such as MD5 and SHA-1, but unfortunately these ones are no longer meant to be used for password storages. Why? Because, although they are still deterministic one-way functions, someone discovered that two different inputs can produce the same hash value (a.k.a collision). This means that there is a possibility that two different passwords can work to access the same account since the computed hash value would be exactly the same.

Here is an example of a collision in the MD5 cryptographic hash function: MD5 Collision Demo.

Hashing Passwords 2.0

Okay, but there should be a cryptographically strong enough hash function right? What if engineers stored passwords using one that provides the following:

- Irreversibility

- Determinism

- Collision resistance

According to the OWASP, there are several functions that can be used such as Argon2 (winner of the password hashing competition), PBKDF2, Scrypt, or Bcrypt. However, this is still not enough.

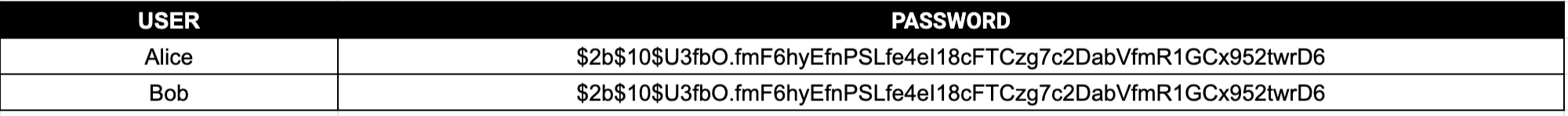

Suppose that the following database that stores hashed passwords using the Bcrypt algorithm is breached.

Site Y’s Bcrypt-hashed database

Even though an industry-recommended hash function is being used, it can be noticed that the hashes are exactly the same. This means that Alice and Bob are using the exact same password. So what if Alice has been already breached and Bob has never been compromised before? As we previously mentioned: All it takes is a breach from Alice’s information in order to get Bob’s password. After all, a chain is as strong as its weakest link.

Do you remember when we took advantage of the following two properties of a good hash function?

- Irreversibility

- Determinism

Well, an attacker could also take advantage of these ones.

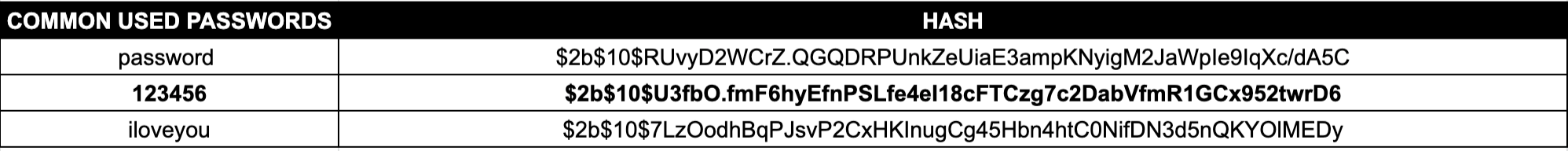

We know that we cannot reverse a hash, but what if we had a huge password list such as rockyou and a compromised database as the one above? Also, what if a user from the database uses a weak password (e.g. one that is in those huge known passwords lists)? In theory, we could see which hash function was used to hash the password, because in this case Bcrypt is open source and it is easy to identify which version and properties were used. In this situation, by using the first 6 characters of the hashed password ($2y$10), anyone can determine that it’s Bcrypt and that 10 rounds were used to hash this password.

This means that an attacker could use a huge list of known passwords and hash them while using the same properties as the passwords in the leaked database (Bcrypt and 10 rounds). And since good hash functions are deterministic an attacker can get a legit hash. These precomputed hash lists are better known as Rainbow Tables. These are huge sets of precomputed tables filled with hash values that are pre-matched to possible plaintext passwords.

My small and awesome rainbow table

Hashing Passwords 3.0 (a.ka Hashing + salt)

Although developers don’t choose other person’s password, they can still add another layer of defense in order to slow down Rainbow Tables Attacks.

To do this, engineers can take advantage of another characteristic of a hashing function: They can be computationally expensive to calculate.

Each time a computer does a hash, it takes up some computational power and this takes time. So what if each time a password is added to a database a random string or salt is appended to it.

hash = strong_hash_function( random_salt + password)

This means that if an attacker finds a database such as the one below, she wouldn’t be able to determine that Alice and Bob are using the exact same password. On top of that, since each salt is different, an attacker would need to perform a dictionary attack for each password with the respective salt combination (salt is not meant to kept secret). This means that it would take even longer to crack a password.

Even though Alice and Bob are using the same passwords, the random salt generates a completely different string.

Salting passwords is a great countermeasure to prevent rainbow table attacks since an attacker would need to have one table for each salt. So, if the database has one-hundred passwords and each one of them has a random salt, an attacker would need to have one-hundred different rainbow tables. This is far from being efficient, since each one of them takes a lot of time to compute and a lot of storage is needed.

Not Storing Passwords

Have you ever signed-in to an application using your Google or GitHub account? Well, there you go. There are times in which applications delegate their user authentication flow to a third party such as Google, Twitter, or Github. These companies have good, easy-to-implement and ready-to-use solutions for authenticating users. So if there is no need to store passwords why would you?

Wrapping it up

Storing (or not) passwords is not an easy task. There are a lot of considerations that engineers need to make in order to implement a safe password storage since a lot of things can go wrong.

It is worth mentioning (again) that a chain is as strong as its weakest link. So what if a password is not strong enough or is in those huge known passwords lists? Remember, even if engineers implement the safest password storage in the world, a weak password will always be an imminent threat.

If you have any suggestions, I would love to hear them. I’m pretty sure we can include more ways on how to design (or not) a safe password storage.

References

https://cheatsheetseries.owasp.org/cheatsheets/Password_Storage_Cheat_Sheet.html

https://danielmiessler.com/study/encoding-encryption-hashing-obfuscation/

https://www.pandasecurity.com/mediacenter/security/password-reuse/

http://www.mscs.dal.ca/~selinger/md5collision/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hash_function

https://passwordhashing.com/BCrypt?plainText=iloveyou

Also published on Medium.

Written on August 20th, 2019 by Sergio Diaz